Warning: Graphic Content

The next morning I awoke, packed, and headed for the airport. I usually like to get to the airport early, but it turned out this was too damn early. The flight was delayed for 5 hours. However, the time was not wasted. Unfortunately, I fucked up my flight reservation flying from Budapest to Belgrade by not using my full first name, much like my initial flight to New Zealand. I realized this when, in my insomniac stupor, I booked my flight through Expedia Ireland. For some reason, the American one was not available. The next day, I noticed the error on my flight itinerary. I wondered if it would be a problem, so I contacted AirSerbia. They said it most definitely was and that I would not be able to fly. I begged and pleaded as much as I could over a chat system. There was a compromise; if I was able to send them an email of my scanned passport. I told them a scanner was not nearby. They told me to find one. Being the resourceful person I am, I took a picture of my passport, made it grayscale, and sent it to them. It worked, and I was not penalized.

I landed in Ho Chi Minh City, aka Saigon. This city was the biggest trophy for the Communists in the civil war within Vietnam. The southern capital was renamed, like Constantinople and New Amsterdam. However, the inner ring of the city still keeps its name of Saigon as a neighborhood designation. That was where I headed.

Much like Hanoi, I was shocked about how modern it was. I got my bags, got my Grab, and headed into the heart of darkness. Much like my accommodations in Hanoi and Hue, the building was not on the street but deep within the labyrinth-like confines of an alleyway. I checked in. To my surprise, the quoted price for my accommodations changed. They increased from $24 a week to a whopping $30. I paid for my stay, dropped my bags, and headed out into the psychedelic night of Saigon.

It is as if I had been transported in time back to the swinging ’60s. Creedence Clearwater Revival played on the loudspeakers of a local bar blaring out onto Bui Van Street. There were bars, girls, drugs, everything that a Young GI could want. For some reason, I was denied entry into a few of these bars but managed to get some dinner consisting of fried bacon. I headed to the end of the block, sat down at a table on the sidewalk in a highbacked wickerchair, ordered a Beer Saigon from a waitress clad in go-go attire, and soaked it all in. After my second round, I headed back to the hostel, caught up on Game of Thrones, and went to bed.

It is as if I had been transported in time back to the swinging ’60s. Creedence Clearwater Revival played on the loudspeakers of a local bar blaring out onto Bui Van Street. There were bars, girls, drugs, everything that a Young GI could want. For some reason, I was denied entry into a few of these bars but managed to get some dinner consisting of fried bacon. I headed to the end of the block, sat down at a table on the sidewalk in a highbacked wickerchair, ordered a Beer Saigon from a waitress clad in go-go attire, and soaked it all in. After my second round, I headed back to the hostel, caught up on Game of Thrones, and went to bed.

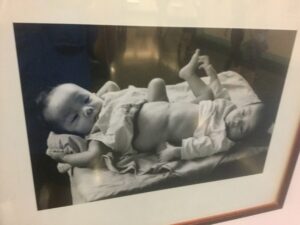

I woke up this morning and had breakfast at the hostel. I then set out for the War Remnants Museum. I thought it would be like the museum in Hue but was surprised by the details with lots of facts and figures. It also had its fair share of macabre, gruesome, and disturbing exhibits. There were graphic photos from the war, including a soldier holding up a freshly exposed ribcage, all that remained of the poor soul that stepped on a landmine. The piece de la resistance was a pair of conjoined twins in formaldehyde, a remnant of the sins of Agent Orange.

General Giap was a diligent student of Sun Tzu’s famous tome of the Art of War. One of the many lessons was about using the environment to one’s advantage simultaneously to the enemy’s detriment. The Viet Mihn, now Viet Cong, used the country’s dense flora as an important tool for waging war. The American’s learned this harsh lesson quickly and subsequently used a previously developed dioxin compound, named for the orange stripes on the barrels in which it was stored. Agent Orange was designed to defoliate the jungles’ trees, disrupt food supplies, and clear areas around bases. However, it did so much more; it killed or maimed almost everything it touched. Millions of Vietnamese and hundreds of thousands of Americans were exposed to Agent Orange, causing cancer, psychological problems, and horrific birth defects.

Another wing of the museum discussed the issues of unexploded ordnance in the country. The United States dropped more conventional bombs on Vietnam during the War’s prosecution than all ordnance used by America in the Second World War. The problem was that not all the bombs exploded. Figures range that 10%-15% of the bombs were defective. The tragedy of this is that these are still killing people as a glossy, technicolor photo of a man with his legs blown off, dated 2003.

Notably absent from the museum was the discussion of the crimes of the Communists, such as massacring villagers, executing civilians, and not prescribing any codified rules of war. But, it was not surprising. The old adage, “To the victor goes the spoils,” should be amended to include “and the histories.” However, America allows both the victors and the vanquished to share their truths, a hallmark of any truly free society.

After the museum, I walked towards “Le Petite” Notre Dame. When the French colonized Vietnam, they wanted some reminders of home. They constructed a beautiful yet much smaller Notre Dame cathedral. At the time, it was the only Notre Dame cathedral in the world that had not been engulfed in flames.

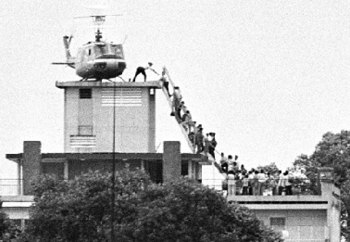

Most people do not realize it, but the iconic photograph of people clamoring on the last helicopters to leave the country as America withdrew from the Vietnam War was not taken on the United States Embassy’s rooftop. The CIA Annex building was where I continued next, located at 22 Gia Long Street. The people that had assisted the Americans during the war knew their days under the Communists would be numbered. They ran, begged, bribed, and pleaded to be taken out of the country. While the Embassy had standard protocols of destroying sensitive documents with shredders, they were not good enough. The Communists took their time reconstructing the documents, then hunted down the people whose names they found contained within. The annex building looked pretty much the same as it did all those years ago.

It was hot, so I headed across the street to a Circle K next to an H & M to grab a Coke. I had only large bills with me. The young girl behind the counter short-changed me by 50,000 Dong. When I called her on it with her manager looking on, she had my correct change ready, stashed under the register. I looked at her and said sternly, “Cam on,” the Vietnamese phrase for thank you, as I walked out.

I walked past the Reunification Palace. This place served at the presidential palace for South Vietnam. After the Americans left, the palace was overrun by the Communist forces using Russian tanks during the Fall of Saigon on April 30, 1975. This was the holiday they were celebrating up in Hanoi. It was the checkmate in this chess game of war that lasted for decades. Vietnam was “reunified” under their single star banner.

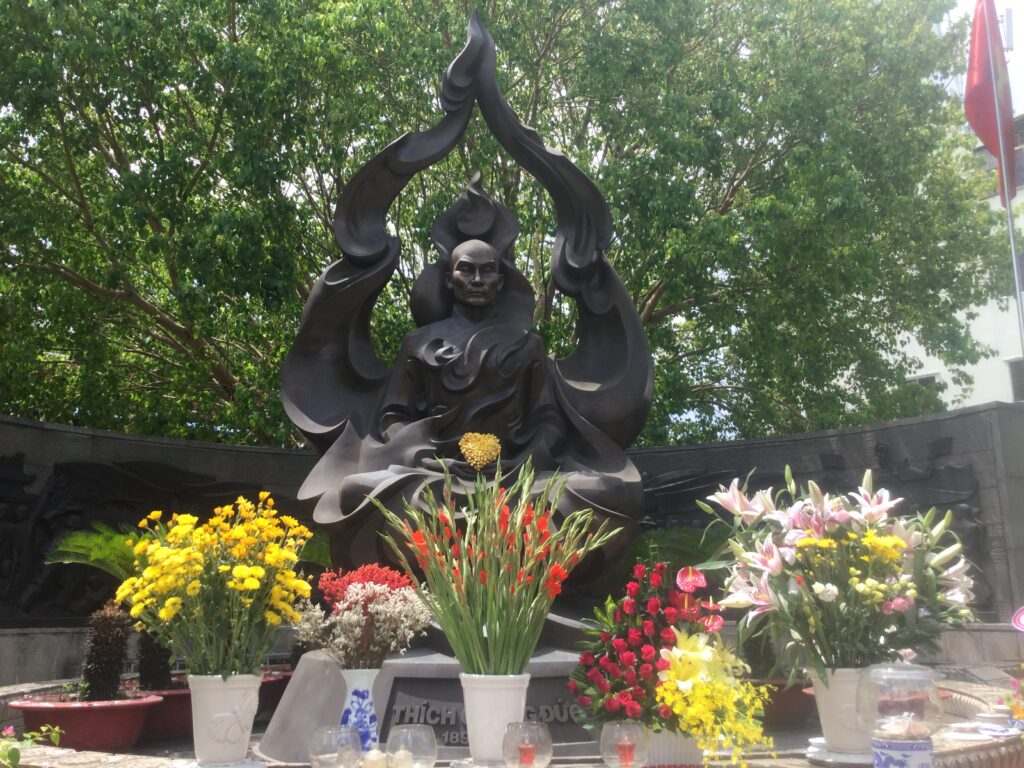

Continuing along my war tour, I went to the site of another famous photograph of the American War, as I learned they called the conflict here. At the intersection of Cach Mang Thang Tam & Nguyen Dinh Chieu Streets on June 11, 1963, the Buddhist monk Thích Quảng Đức arrived from Hue in a baby blue sedan. Calmly leaving the car, he sat in the lotus position in the middle of the intersection as a colleague poured gasoline on him, spoke the words “Nam mô A Di Đà Phật” (“Homage to Amitābha Buddha”), struck a match, and self-immolated. He made no other sound.

Like most instances in history, conquering powers tend to impose their religious practices on the conquered. Vietnam was no different. There is Catholic population in the country due to a history of imperialism, but they are the minority. Those that adopted the ways of the colonizers were awarded positions of power. Those that remained with their supposed ancient superstitions were denied power and even representation. When Buddhists came out to celebrate Buddha’s Birthday birth in Hue in 1963, an illegal act in President Ngo Dinh Diem’s Vietnam, he sent the police then the army to quell the celebration turned protest. Nine people, including two children, were killed in the incident. That is what Thích Quảng Đức was protesting in his peacefully violent way. It was this act that steered the hearts and minds of the world to Vietnam.

I walked the few miles back to my hostel, took an icy shower, and decided to have myself a little Vietnam movie marathon. I had some work to do, so I went and got dinner. I also got a beer, enjoyed it on the hostel’s rooftop, and then got to work.

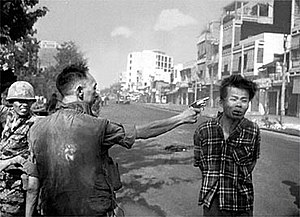

The next day, I woke up, had breakfast, and headed out to see the spot of yet another iconic photograph from the Vietnam War. In the afternoon of February 1st, 1968, a person in civilian clothes was marched to General Nguyễn Ngọc Loan on a busy Saigon street, 252 Ngo Gia Tu Street District 10. General Loan nonchalantly pulled out his Smith and Wesson revolver, put it to the man’s head, a pulled the trigger. All while AP reporter Eddie Admas was taking photos and his crew was filming, later receiving a Pulitzer Prize. America and the world were shocked by the brutality and the supposed cheapness of life in America’s already protracted and haphazardly fought the war. What the photo does not relate is the events leading up to that fateful shutter flash.

General Loan rose through the South Vietnamese army ranks by merit, not through the usual nepotism that was rampant in the South’s government. He led combat operations in the North both as a pilot and on the ground, all of which left him adored by his men. He also hated Communists.

The early months of 1968 were the height of the Tet Offensive. General Loan was tasked with supporting the local police forces as hard and soft targets were attacked all over the country. On the morning the photo was taken, 34 people were killed, including police officers, their families, including small children, older adults, and several Americans. Some were bound, shot, and thrown in a pit while the Viet Cong briefly over-ran Saigon, settling scores. Nguyễn Văn Lém, also known as Captain Bay Lop, was the death squad’s head, the executed man. He had just slit the throats of a police officer’s entire family. He wore no uniform, was a terrorist, and committed war crimes. All of which were the reasons for immediate execution as he had no protections under the Geneva Convention. General Loan was personally out on the streets looking for at-risk targets and the Viet Cong guerillas looking to harm them. No doubt, friends and colleagues were laying in pools of their own blood due to this man’s acts, the Captain. People were wondering why I was standing on this non-descript street for so long taking photos.

I then stopped at the Ben Than market to look around, but it was a tad overwhelming, and I really did not need or want anything. I walked back to my hostel after buying a large beer and large water. After my respite, I went around the corner from my hostel and had a fantastic lunch for $3.50. I then walked back down Bui Van Street on my way to another bar in the afternoon. While I was walking, a young lady was out in the streets offering massages. I walked down the opposite sidewalk when she hurriedly crossed the busy street and forcibly grabbed me by the arm, lightly digging her nails in, demanding that I come for a massage. I jerked my arm free from her grip, sternly pointed at her saying no, then continued on my way. She yelled something in Vietnamese as I kept walking. No doubt her income depended on how many customers she could bring in, but I was still half-expecting to get lye in a Coke here, a popular practice by the Viet Cong of poisoning American soldiers.

I arrived at the bar with a patio upstairs and watched the frenetic traffic of Saigon pulsate on the street below. I had my beer, carefully walked back to my hostel, and just vegged out for the rest of the day.

The next day, I got up early as I booked a tour to the Cu Chi Tunnels and to see the Mekong Delta. I went to the Circle K to get some supplies. The van showed up 15 minutes late, but that was OK. The tour guide Vu was very nice and encouraged questions. My van mates and I headed to the outskirts of Saigon. The first place we stopped was a little factory of crafts. Agent Orange is still harming people. While the numbers are reducing for every generation, many are still born with congenital disabilities. This little craft factory was a place that hired only these types of people to make souvenirs and keepsakes. The proprietor said that these people want to work so they will not be burdens on their families. I watched a man with deformed arms and hands arrange mother of pearl inlays with tools held by his feet.

The next day, I got up early as I booked a tour to the Cu Chi Tunnels and to see the Mekong Delta. I went to the Circle K to get some supplies. The van showed up 15 minutes late, but that was OK. The tour guide Vu was very nice and encouraged questions. My van mates and I headed to the outskirts of Saigon. The first place we stopped was a little factory of crafts. Agent Orange is still harming people. While the numbers are reducing for every generation, many are still born with congenital disabilities. This little craft factory was a place that hired only these types of people to make souvenirs and keepsakes. The proprietor said that these people want to work so they will not be burdens on their families. I watched a man with deformed arms and hands arrange mother of pearl inlays with tools held by his feet.

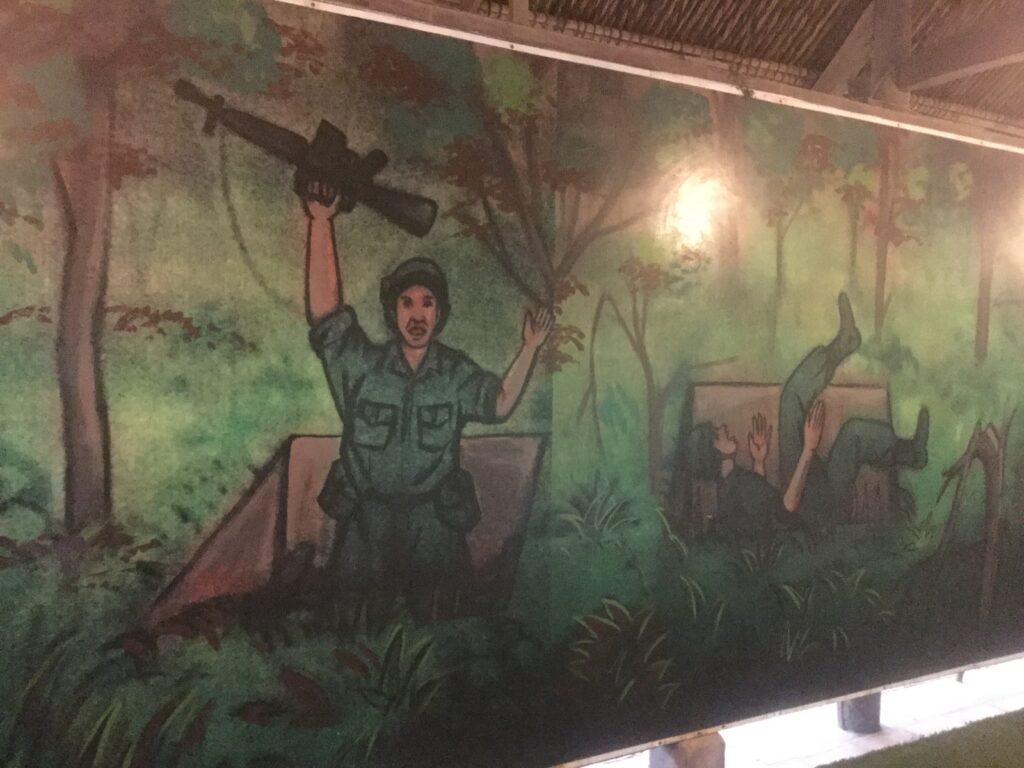

After this, we headed to the Cu Chi Tunnels. Much like in Vinh Moc in Hue, these tunnels were dug into the soft Earth. But that is where these similarities end. While the Vinh Moc Tunnels were for defense, these were strictly for the offense. The Cu Chi Tunnels were the end of the Ho Chi Minh trail and were insidiously protected. Arms and supplies were stored here so that assaults could happen well within enemy lines. This was the work of the Viet Minh, the guerilla army fighting against the French, which was then soon adopted by the Viet Cong, the guerilla army fighting the Americans.

As we drove, Vu showed us a film talking about the tunnels. An Australian asked my thoughts on the propaganda aspects of the film we saw on the way, particularly headlining Vietnamese teenagers killing scores of American soldiers. I told him it was exactly that, propaganda.

We arrived at the Tunnels, with the sound of gunfire filling the air. It appears Vu forgot to mention that there was a live-fire range where tourists could try out some of the hardware from the war from both sides. Since Vu was a licensed tour guide, he showed us around. It was bizarre, to say the least. Looking like a Communist Disneyland, they had animatronic Viet Cong soldiers dismantling unexploded ordinance and removing the explosives for later use or fashioning the leftover metal into boobytraps. Another exhibit showed in graphic detail all the types of boobytraps used. These included punji sticks – buried and lightly covered fecal matter smeared sharpened bamboo, tiger traps – more sharpened bamboo in a pit with a rotating top, and various other low-tech devices. A mural of maimed and bloodied American soldiers crying in anguish as their comrades helplessly looked on comprised the exhibit’s back wall.

We arrived at the Tunnels, with the sound of gunfire filling the air. It appears Vu forgot to mention that there was a live-fire range where tourists could try out some of the hardware from the war from both sides. Since Vu was a licensed tour guide, he showed us around. It was bizarre, to say the least. Looking like a Communist Disneyland, they had animatronic Viet Cong soldiers dismantling unexploded ordinance and removing the explosives for later use or fashioning the leftover metal into boobytraps. Another exhibit showed in graphic detail all the types of boobytraps used. These included punji sticks – buried and lightly covered fecal matter smeared sharpened bamboo, tiger traps – more sharpened bamboo in a pit with a rotating top, and various other low-tech devices. A mural of maimed and bloodied American soldiers crying in anguish as their comrades helplessly looked on comprised the exhibit’s back wall.

After this, we took a little break for refreshments before actually heading down into the tunnels. As a man of 6ft and 180lbs, it became apparent that these tunnels were not made for me. Seeing how a Vietnamese man’s average height is more than 6 inches shorter and 60 pounds less, these tunnels were designed for small, skeletal soldiers that derived sustenance from a handful of rice and, if they were lucky, rat meat. Cu Chi was even smaller than the Vinh Moc Tunnels. For the first time in my life, I got claustrophobic. But I pushed through, got down on my hands and knees, and kept going through the darkness until I got out, not thinking about the feelings I was having. I emerged relieved, and we went and had lunch.

After this, we headed to the Mekong Delta. We got out of the van and took a ferry over to a little farm selling homemade honey that they let us a sample. They also let us hold their 12 ft python for photos. We then took a horse-drawn cart to a cultural center where we tried local food as Vietnamese folksongs serenaded us. Afterward, we were paddled back out to the delta.

During my 4 month stint as an Uber driver, putting in close to 10 hours a day, every day, I used the image of this moment to keep me going. And here it was happening. It was a wonderful feeling.

As the tour was over, we hopped in the van and went back to Saigon. I got some dinner at the only local restaurant that accepted credit cards, then got dessert at the Circle K. I headed back to the hostel to finish up some work. All in all, it was a great day full of insight.

The next day, I woke up with no real plans, so I decided to have Mr. Bourdain be my guide again. I walked close to 3 miles to pay my respects to The Lunch Lady of Saigon. I followed my Google directions to the T but was unable to find her restaurant. I then heard a din from a parking lot behind the building. It turns out this was not a restaurant but an outdoor tent where she served her food. They sat me down at a crowded table and took my order. I took Anthony’s advice and got the Bun Bo Hue to compare it to the one I had in Hue. Before they brought me my soup, they put food down in front of me that I did not order. These included fried spring rolls and some shrimp cake. After a few more minutes, they brought out the Bun Bo Hue. It was comparable to what I had eaten before. As I was full, I gave my shrimp cake to my table partner that looked like he could use it.

I walked back to my hostel, taking the long route around the city. I relaxed after traversing the spring heat of Saigon. I noticed that a screw on the under chassis of my MacBook had come loose and was missing. In my walks around Saigon, I noticed there were a few Mac repair places nearby. I went to one, and he said he had no screws. I went to another, and they said they had them. So, I returned to my hostel, got my computer, and walked back. When I returned, the clerk told me he did not have any screws. Dejected, I turned back around. He felt bad, so he told me to wait a minute. I took a seat as he went into the back room. He returned with a single, solitary screw and a screwdriver. He installed it. I asked him how much it was. He smiled and told me it was on the house. I still gave him a tip and headed back out into the early spring evening in South East Asia. I had dinner at my new favorite local restaurant right around the corner from my hostel, took another shower, then watched Platoon as I did some work. The heat was draining, so I went to bed.

“Saigon, shit, I’m still only in Saigon. Every time I think I’m gonna wake up back in the jungle.”

Not going to lie; Vietnam and Saigon in general are grinding on me. But, good news! I found my missing computer screw. I had to install it with the aid of one of my many pocketknives. I got up late and headed out to the Hotel Continental and had some tea as I overlooked the Saigon Opera House as an homage to The Quiet American. Unfortunately, while I was there, enjoying my tea at a street-side table, I was accosted by two shoeshine boys and a young girl holding a baby selling fans. They did not leave with a simple shake of the head and putting a hand up. It took about 3 minutes each of ignoring them as they were in my face before they cursed me in Vietnamese and moved on.

Not going to lie; Vietnam and Saigon in general are grinding on me. But, good news! I found my missing computer screw. I had to install it with the aid of one of my many pocketknives. I got up late and headed out to the Hotel Continental and had some tea as I overlooked the Saigon Opera House as an homage to The Quiet American. Unfortunately, while I was there, enjoying my tea at a street-side table, I was accosted by two shoeshine boys and a young girl holding a baby selling fans. They did not leave with a simple shake of the head and putting a hand up. It took about 3 minutes each of ignoring them as they were in my face before they cursed me in Vietnamese and moved on.

After, I went to my final Bourdain recommended place in Saigon. It was another outdoor restaurant selling bahn xeo. Bahn xeo is basically an egg pancake, a crepe if you will, with sprouts, shrimp, and other meat that one wraps in a lettuce leaf before eating. The kitchen was open, so you could see the women huddled over their woks, working very hard to make sure that each came out just right. They were delicious.

As I was walking back to my hostel, there was a souvenir shop. Passing the display table on the sidewalk, I noticed a small metallic trinket. Without further hesitation, I knew what it was. This stand was selling American military dog tags. Some were worn. Some had holes. I beckoned to the woman running the store, and she came over. I asked if she spoke English. She said a little. I pointed to the dog tag and asked how much they were. She told me 700,000 Dong. I did a quick calculation in my head. An American soldier’s life and death were worth $30 to this woman on a dusty street in Saigon.

I could not get back to the hostel fast enough. I was fuming. I got some beers and then hung out in the lobby of my hostel. There were some other travelers, but they paid me no mind. I took a shower, got in bed, and relaxed.

After, I went out for dinner at my local place, walked around, and found someone selling mango for dessert. I then walked down Bui Van Street. I did not notice before that the bars here also happened to sell Nitrus Oxide, an anesthetic often used for dental surgery. As I walked further, a massage girl tried to take my hat. I had had it with Saigon. I went home, took a shower, and went to sleep.

After, I went out for dinner at my local place, walked around, and found someone selling mango for dessert. I then walked down Bui Van Street. I did not notice before that the bars here also happened to sell Nitrus Oxide, an anesthetic often used for dental surgery. As I walked further, a massage girl tried to take my hat. I had had it with Saigon. I went home, took a shower, and went to sleep.

The next day was my last full one in Saigon. I had brunch at my local restaurant, The Royal. I had a fruit bowl and a big steamy bowl of pho. I tried walking a little, but it began to rain. I ducked into a restaurant that just happened to be named Obama’s Bun Cha. This was a counterfeit version of Bun Cha Huong Lien from Hanoi, but it shared the same decorations of the former president’s glossy photos. Since it was storming now and had nothing better to do, I sat down and had some pretty good Bun Cha.

Since the next day I had a four-hour-ish ride out of the country, and my GI tract can be unreliable, this would be my last meal in Vietnam. I headed back to the hostel and chilled for a few hours. The rain continued, and as I looked out to this back alley, it reminded me of one of those long rainy afternoons in New Orleans when an hour isn’t just an hour—but a little piece of eternity dropped into your hands. Apres le deluge, I wanted to find the place where I would be grabbing the bus the next day. The rain had cleared, and I headed out for the final night’s entertainment on Bui Van Street. I sat at the first bar I went to in Saigon, G02, as the technicolor psychedelic madness engulfed me for the last time.