After a bit of a restless night, I headed back downstairs for my final free breakfast. I started chatting with a guy who was at the hostel for the same duration I was, but we never really spoke to each other before. He had just graduated from UCLA and was also leaving Hanoi that day. If I felt like a giant walking amongst the Vietnamese, he must have felt like Godzilla. Standing at 6’7″, the country was not built for him. After a leisurely conversation in some of the hostel’s supplied hammock chairs, we stored our bags and headed for a coffee right around the corner from the hostel. While we sat there, some gentlemen wheeled another mobile amplifier on the street and started a round of karaoke. After this, he and I had some last-minute errands to run. I went back to Returned Sword Lake, where there was a waiting post office, and mailed postcards to my nephews and friends that had inspired me to come to this part of the world. I found my big friend again, and we decided to have lunch. As he was tired of noodles, I suggested my com place. He seemed to enjoy it. After lunch, he told me about his plans of travel. Vietnam has an interesting mode of transport between cities. The night bus is like a regular bus; however, there are beds fitted for the standard-sized Vietnamese person instead of seats. My friend was slated to take a night bus somewhere, and understanding that he was a rather large man, he foresaw that it would be a restless night. Probably with his knees by his ears. As such we decided to take advantage of the interesting practice in many developing countries of being your own pharmacist. We went to a local pharmacy where he tried to buy some Ambien but settled on a few tabs of Xanax. We talked some more before I had to grab my bags and bid him adieu. I got a Grab and headed back to the airport. I was a bit more emotionally prepared for the journey this time.

I passed through security with no problem. I found my gate and waited for my already twice-delayed plane. Having watched Apocolypse Now with a new understanding of the war, I blasted The Doors as I walked around the airport for a bit, looking at all the interesting souvenirs. I then boarded my Vietnam Airlines flight to Hue.

I landed in Hue at night. As is the custom in most parts of the world, I deplaned to be transported by a people mover to the terminal. As soon as I left the fuselage, looking out from my perch atop the wheeled stairs, I got an incredibly eery feeling. At the edge of the airport, spotlights were facing towards the runway and the terminal. But beyond those lights was nothing but tall grass and darkness. It was as if for a brief moment, an ancient, instinctual fear overtook me, as I am sure it overtook many foreigners when they came to this place. While I could not peer through the darkness, the darkness and all it contained felt as if it were peering through me. My step quickened as I got on the people mover and headed to the terminal.

Hue Airport was not as impressive as Hanoi’s. It was a small airport only large enough for a maximum of two planes unloading at once. I got my bags and was able to get wifi to secure a ride to my hotel. As Hue rolled before me in the night, it was more of what I was expecting Vietnam to be; lots of stores and homes along the dusty shoulders of the main highway. About 45 minutes later, I was dropped off at the mouth of a dark alley. Apparently, my hotel was almost at the end of it.

I always tried to arrive at my destination while the sun was still in the sky. Seeing how it was at night made me very nervous walking down an alleyway with my bags. The alley had apartments and homes lining it and a completely shaved husky dog for some reason, so my fears quickly dissipated. I continued until I found the footpath that lead to my hotel. I knocked on the door. They opened it, checked me in, served me a watermelon drink, and showed me to my room. It was GREAT. I had a queen bed, air conditioning, television, AND A BATHTUB! While the watermelon drink was nice, I needed something a bit stronger. I dropped my bags and headed out for supplies. I bought myself a local beer called Huda and headed back to enjoy it in the tub. The enjoyment was short-lived. Apparently, the bathtub was not secured to the floor, and the drain was not affixed to the tub. By getting into it, I dislodged it. Instead of the tub draining down a pipe, it drained on the floor. I threw down some towels and called it a night, stretching out in my queen bed with the air conditioning making my room like the arctic tundra.

Hue, unfortunately, sits in the middle of a country that defines itself as either being North or South. Nestled along the Perfume River, it also was the old imperial seat. It would be fitting to call it the Boston of Vietnam, as it is home to their most famous university and other higher learning institutions. The upper echelons of both sides of the eventual conflict matriculated there. Why Hue is important, at least in regards to the Vietnam War, is that while most of the war was prosecuted in the jungles and hamlets of the countryside, this was the theater of urban combat televised back to American living rooms and shown in the film Full Metal Jacket. I found out more recently that a family friend used to patrol the rivers and inlets out of Hue in a swift boat for three tours. The Christmas before I left, my uncle gave me a fantastic book entitled Hue 1968 by Mark Bowden. The card read, “I was parked off of here in the Navy and listened to Tet live.” Hue was the focus points of the infamous Tet Offensive in 1968. After a few years of fighting, a cease-fire was negotiated for the Lunar New Year celebration of Tet. However, only one-side lived up to the agreement. The Tet Offensive was the brainchild of perhaps one of the greatest military minds of a century filled with them, General Vo Nguyen Giap. It was a unified, coordinated strike against many American and South Vietnamese military installations and personnel all over the country, even in the supposedly secure capital of South Vietnam, Saigon. Hue and the surroundings were hit especially hard as they were located on the border of North and South.

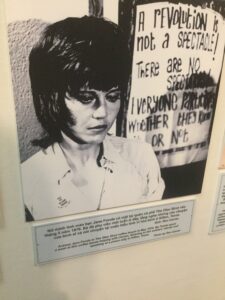

Today, I woke up very early but had no idea why. I called my mother to let her know how I was, as the time difference was beneficial. Afterward, I headed to the Hue War Museum across the Perfume River. What drew me to it was all the tanks and airplanes that were Vietnam War vintage parked right out front.. However, upon closer inspection, each had a plaque saying from where they were “liberated” and the date. Most were the same, all from the former United States Air Base in De Nang well after the war.  These machines were just left there as the mighty United States retreated. Inside the museum, there was another wing that I found very interesting amongst all the displayed arms. It discussed the American protest movement as Ho Chi Minh’s 5th Column to sabotage the war effort from within the United States. Hanoi Jane Fonda was front and center in this part of the museum. The actress Jane Fonda of 60’s Barbarella fame actively spoke out against the War for the uninitiated. She even went as far as to visit Communist North Vietnam and took photos of her in a helmet sitting at an anti-aircraft gun used to shoot down American planes. Needless to say, this demoralized a lot of the fighting men, just as Ho Chi Mihn would have wanted.

These machines were just left there as the mighty United States retreated. Inside the museum, there was another wing that I found very interesting amongst all the displayed arms. It discussed the American protest movement as Ho Chi Minh’s 5th Column to sabotage the war effort from within the United States. Hanoi Jane Fonda was front and center in this part of the museum. The actress Jane Fonda of 60’s Barbarella fame actively spoke out against the War for the uninitiated. She even went as far as to visit Communist North Vietnam and took photos of her in a helmet sitting at an anti-aircraft gun used to shoot down American planes. Needless to say, this demoralized a lot of the fighting men, just as Ho Chi Mihn would have wanted.

After I had my fill on propaganda, I went back to the hotel and took a nap. I got up and decided to walk around the other side of Hue after having lunch. There was a footpath next to a road that went along an isthmus. I found a little place to have lunch and stared out at the water. I was more concerned about the food and drink here than when I was in Hanoi, but everything seemed OK. I walked farther in this new part of town, past shops, restaurants, and seemingly dilapidated temples. From as far as I could tell, even though “religion is the opiate of the people,” there seemed to be a tolerance for it, including Buddhism. As the Buddha’s birthday was coming up, people left incense to dry on the sidewalk and prepared fake $100 bill offerings for prosperity. As I reached the outskirts of this side of town, I turned around and headed back from whence I came. I found the touristy section of Hue, which, sad to say, made me feel more comfortable after seeing other tourists that looked like me. I found a bar and wrote a postcard to my Uncle Billy, the uncle that had the front row seat to Tet. I found some more postcard stamps for friends, had another beer, then went to find some dinner.

After I had my fill on propaganda, I went back to the hotel and took a nap. I got up and decided to walk around the other side of Hue after having lunch. There was a footpath next to a road that went along an isthmus. I found a little place to have lunch and stared out at the water. I was more concerned about the food and drink here than when I was in Hanoi, but everything seemed OK. I walked farther in this new part of town, past shops, restaurants, and seemingly dilapidated temples. From as far as I could tell, even though “religion is the opiate of the people,” there seemed to be a tolerance for it, including Buddhism. As the Buddha’s birthday was coming up, people left incense to dry on the sidewalk and prepared fake $100 bill offerings for prosperity. As I reached the outskirts of this side of town, I turned around and headed back from whence I came. I found the touristy section of Hue, which, sad to say, made me feel more comfortable after seeing other tourists that looked like me. I found a bar and wrote a postcard to my Uncle Billy, the uncle that had the front row seat to Tet. I found some more postcard stamps for friends, had another beer, then went to find some dinner.

The next morning, I woke up at 6 am as I booked a tour to visit the DMZ. Much like in Korea, when the country was divided, there was a demilitarized zone along North and South. My driver picked me up at 7 am, and then we had an hour drive to pick up my guide in Dong Ha. The first stop we made was the Lady Vang Holy Site.  In 1798, many persecuted and diseased Catholics were living in the jungle and prayed for succor from the Virgin Mary. Under a banyan tree, Mary appeared, cured their pestilence, and gave them medicine. She told them to pray to her there, and all their ailments of body, heart, and soul would be healed. A holy site was subsequently erected. This day, there were people on their knees praying, hugging the statue, and pressing their heads to it in deep contemplation. It was a sight to behold. There was even a chapel nearby that played hymns in Vietnamese through loudspeakers.

In 1798, many persecuted and diseased Catholics were living in the jungle and prayed for succor from the Virgin Mary. Under a banyan tree, Mary appeared, cured their pestilence, and gave them medicine. She told them to pray to her there, and all their ailments of body, heart, and soul would be healed. A holy site was subsequently erected. This day, there were people on their knees praying, hugging the statue, and pressing their heads to it in deep contemplation. It was a sight to behold. There was even a chapel nearby that played hymns in Vietnamese through loudspeakers.

We continued to Dong Ha and picked up our guide, Thach, and headed out. We drove past The Rockpile, a Marine Base located at the top of a steep rock face, only accessible by helicopter. We then drove past the Dakrong Bridge, a former crossing point of the Ho Chi Minh trail, a multi-national, enemy supply network winding from North to South transporting munitions, supplies, and equipment usually by foot. We then continued to Khe Sahn.

We continued to Dong Ha and picked up our guide, Thach, and headed out. We drove past The Rockpile, a Marine Base located at the top of a steep rock face, only accessible by helicopter. We then drove past the Dakrong Bridge, a former crossing point of the Ho Chi Minh trail, a multi-national, enemy supply network winding from North to South transporting munitions, supplies, and equipment usually by foot. We then continued to Khe Sahn.

Khe Sanh was a Marine combat base built-in 1962 that gained infamy as one of the hardest-hit places during Tet. Upon arriving at Khe Sahn, the first thing I noticed was the noise. Being in such a remote part of Vietnam close to the Laos border, the cicadas sang a deafening foreboding dirge. I walked around the skeleton of this once formidable base after stopping in their tiny museum. There were enclosures and trenches, even a runway. There was also a gentleman there selling medals he found in the fields nearby. The guns of Khe Sahn were still facing Laos. I knew many a Marine probably felt like I did when I was at the airport in Hue at this base, staring out into the darkness full of terrors wondering what or who was looking back.

After Khe Sahn, we headed back to the coast to grab lunch. We then went across the river dividing North and South Vietnam on our way to the Vinh Moc Tunnels. Bombing Vietnam back to the Stone Age happened here, especially. In response to this, the locals dug 6000 cubic meters of clay as deep as 2 meters to protect them from bombardment. They had ventilation as half the entrances faced the mountains and the others faced the sea. Families lived in their clay apartments at night but still worked during the day in the rice fields. There was a hospital, maternity ward, an open space for a school, cinema, and performance area. At its peak, 500 people lived there. They even had drainage. As Thach and I followed the path out towards the sea, she mentioned that she had another American on her tour a few years ago by the name of Anthony Bourdain and asked if I had heard of him. I smiled and told her that yes, I had heard of him.

After Khe Sahn, we headed back to the coast to grab lunch. We then went across the river dividing North and South Vietnam on our way to the Vinh Moc Tunnels. Bombing Vietnam back to the Stone Age happened here, especially. In response to this, the locals dug 6000 cubic meters of clay as deep as 2 meters to protect them from bombardment. They had ventilation as half the entrances faced the mountains and the others faced the sea. Families lived in their clay apartments at night but still worked during the day in the rice fields. There was a hospital, maternity ward, an open space for a school, cinema, and performance area. At its peak, 500 people lived there. They even had drainage. As Thach and I followed the path out towards the sea, she mentioned that she had another American on her tour a few years ago by the name of Anthony Bourdain and asked if I had heard of him. I smiled and told her that yes, I had heard of him.

We then headed to the Hien Luong Bridge, the classic cold war bridge over the Ben Hai river. Basically, a pissing match in wood and metal. After I went through the mostly propaganda-filled museum, there was a pedestrian path on the bridge, and Thach invited me to walk with her back to the South. A giant statue in the distance wrapped in friscalating dusk light was surrounded by people’s drying rice laid out on the concrete.

The tour was winding down, and we drove Thach back to her house. I noticed that many Vietnamese flags in the area were at half staff or draped in black. I asked why and Thach said it was because a local party boss died. Suspiciously. I knew not to ask further. We dropped off Thach, and an hour later, I arrived at my hotel. I took a shower, dropped off my laundry with the staff, then headed out for dinner. I took a long walk by the river where I helped two sets of students with their English homework, like when I was back in Japan. Anchored, lighted lotus blossoms decorated the Perfume River as a celebration of the Buddha’s birthday. I had a nightcap at the aptly named DMZ Bar.

The next day, I woke up and headed out for breakfast. Close to the hotel in Hue seemed to be a tourist mecca with many bars, restaurants, and clubs. There was even a mock 1950’s American diner. I found a little coffee shop and had myself a coffee and a liquid yogurt drink which was pretty delicious. I then did some research to find Bun Bo Hue.

Bun Bo Hue is characterized as a beef soup with rice vermicelli noodles. The cuisine is closely associated with Vietnam’s royal court and has a lemongrass flavor mixed with salty and spicy layers. Of course, my favorite chef pointed me in this direction.

The Bun Bo Hue that Anthony had was located in the Dong Ba Market, back across the river. In the 90s, at 10:30 am in the early May sun, I trekked back across the Perfume River. For those that have not visited an Asian market, it is ordered chaos. Stalls etch out where they can, and there is little rhyme or reason why some stores are close to each other. Being sure to follow the directions (right at the flower stall at entry, left at the guy selling leather goods), I found the Bun Bo Lady of Hue. I sat down at the stall, already covered in sweat. Without missing a beat or even taking an order, the lady plopped down in front of me some grilled meat skewers and a beer. I did not have to say anything; she knew what I was here for. After a few minutes, the hot soup was placed in front of me. Thanks to my father’s guidance, I have always been an adventurous eater. But here, I really leveled up. Never in my life had I eaten in a place where large, well-fed rats ran across my feet. Luckily, the soup was very much worth it. I thanked the lady and paid. As it looked like I had fallen into the river with all my clothes on, she gifted me a free bottle of water on my way out. She was very generous.

Unfortunately, nature called, and I was a few miles from home. I ran to a nearby supermarket to find a bathroom and came to the most basic realization about life in a Communist/developing country: toilet paper can not always be expected.

Relieved, I decided to check out The Citadel and find out exactly why the Marines were forced to do house-to-house fighting, as leveling the Hue was not in the rules of engagement. I walked around the Imperial City and was very much impressed by its size and grandeur. Protected by a series of walls, moats, and ramparts, the royal family lived here since the 1800s after the country was finally, if yet prematurely, declared united. The Imperial family bellowed during the winds of change and bowed to the whims of invading forces: the Chinese, the French, and eventually handed the keys directly over to the Communists in 1945. The royal name is Nguyen, which explains why there are so many in the US. Upon entering the grounds, I was taken back at the stark contrast. There were trees, gardens, and palatial palace buildings. A lot of it was influenced by Chinese architecture. It was only natural that the structure would be used for defenses, even well after the Imperial family left. During the Battle of Hue, it served as an important rally point for the People’s Army of Vietnam and Viet Cong, with bullet holes still visible on the outer walls to prove it.

After my personal tour, it reached 100 degrees again, so I schlepped back to the hotel to cool down. Along the way, I noticed that some fantastic-looking garments in shops lined the streets heading back to my hotel that I never noticed before. I would later learn they were called Ao Dai, former tunic-like clothes of the royal court. Today, they are a traditional yet popular fashion style among women and are gorgeous.

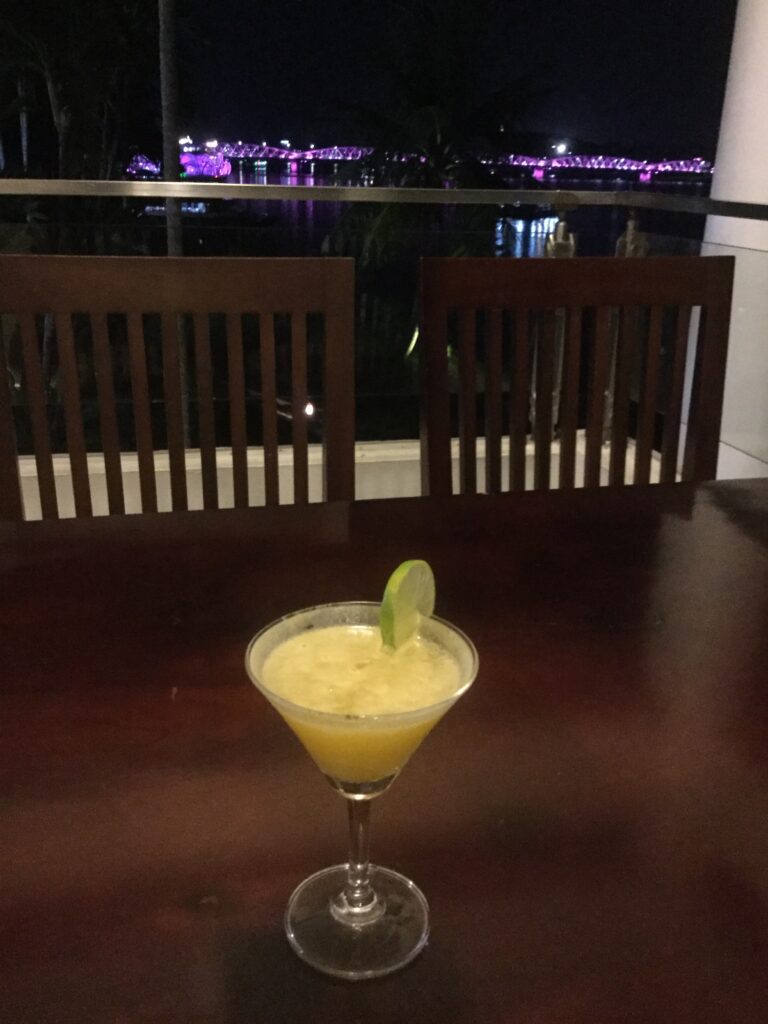

Upon arriving at the hotel, I hung out, took a shower to cool down, then headed out to get some Bahn Mi. I sauntered into the Century Hotel to have a cocktail and watch the Perfume River and the changing colors of the Cau Truong Tien Bridge, like the Busan Harbor Bridge or Rainbow Road. I walked around the tourist district, making sure to buy a shirt for myself. I then headed back to the hotel for possibly one of the most important conversations of my life.

A few different people managed the hotel bar, but tonight would prove to be auspicious. The bartender was a kid, probably in his teens. He spoke English very well, and after serving me my new favorite Huda beer, we began talking. I was right; he was in his teens and just finished high school. He told me he learned English by watching YouTube videos, listening to music, and watching movies with subtitles. In as friendly away as I could, I asked him what he thought about Americans. He looked around the room to make sure that no one listened to us and fiddled behind the bar. He produced a lapel pin of the flag of South Vietnam conjoined with the American flag from his wallet. He told me he loved America. He explained to me this trinket was given to him by a returning American Marine who had fought and lost friends in Hue. More importantly, he shared that if he were caught with it, he would go to jail. He then shared with me the plight of his family.

His father and uncle were both members of the South Vietnamese Army in Saigon. When the Americans left Vietnam, this boy’s father and uncle had a bonfire in their backyard and destroyed every piece of identifying information they had, especially their uniforms. They waited for a knock on the door in the middle of the night for two years. When that day came, both were taken by the central authority and given an option: Be “re-educated” or go the Hue to do manual labor for the rest of their lives. Since re-education meant certain death, they both accepted their fate and moved to Hue. Life was not so unbearable for them. After a few years of toil in the Vietnamese sun, they proved they were loyal Communists and hard workers without complaint. The authorities left them alone. His father met his mother and married, with he being the fruit of their union. Unfortunately, his father died when the bartender was young, no doubt from then already years of backbreaking labor in the sweltering heat. Being the man of the family at such a young age, he needed to help his mother run their Bahn Mi cart, but she forced him to go to school and encouraged him to learn English. He then thought, what better place to practice than at a hotel. His cousin’s friend’s friend knew someone at the hotel, which is how he got the job. He worked his way up from cleaning the rooms, doing the laundry, to cooking, then finally to bartender. What he told me next would put everything into perspective.

He leaned in and told me he hated Communism. He talked about how corrupt the government was. He described the various ways they blow all the money they take from the people instead of doing at least the bare minimum of what these socialists promise: free healthcare, free education, and taking care of the old. Even though his father and uncle were able to get back in the government’s good graces, there is still a black mark on the family. If it is anything like North Korea, it will be the bartender’s grandchildren that will finally be “free.” He cannot travel outside of the country as it is costly. Even if he had the money, he would not be able to get an exit visa due to his father’s counter-revolutionary sins. His curse is to remain in the People’s Republic until he dies.

This all broke my heart. So much so, I asked him what his monthly salary was. He told me. I told him to pour me another Huda and that I would return. 10 minutes later, I came back. I told him was going to turn in for the night. He gave me my bill, and I, having come from an ATM, gave him a month’s salary tip. I shook his hand, leaned in, and told him that I would pray for a free Vietnam, for him and his family. He thanked me with a tear in his eye.

I walked up to my room and thought about the gravity of the conversation I just had. I took another shower and went to bed. This was my last night in Hue. Saigon in the morning.