Today, I left Kyoto for my bus ride over to Hiroshima. It was a very good thing I arrived early as the bus stop was not properly marked. I tried my best to find out asking around, but no one spoke English or knew where I should go. I walked to each terminal around the time we were supposed to leave and finally found the one. I pulled out my phone, the driver scanned the ticket, and I was set. The ride was smooth, as had become the usual touring the highways and byways of Japan. I arrived in Hiroshima and immediately set out for my hostel. It was about 3:30 pm, and after a nice lady pointed me in the right direction, it was only about 10 minutes away from the bus terminus. The hostel was on top of a bar/restaurant, which was great because each night we had a cocktail on the house. After I interrupted a staff meeting, I was shown my pod.

My things secured, I headed out to take a little personal walking tour of Hiroshima. I had seen this city countless times in black and white photographs, before and after shots, and even from bombardier doors. It was something completely different strolling these streets, smelling the fragrant air, and listening to families have picnics along the riverbanks.  A streetcar passed, reminding me very much of New Orleans. I would come to learn that these cities would share more similarities than just transportation. I got dinner at a Lawsons, a competitor to my beloved 7-11, then headed to another competitor, Family Mart. Since it was cherry blossom season, Family Mart had a unique cherry creme-filled croissant which was possibly the best continual thing I ate while in Japan.

A streetcar passed, reminding me very much of New Orleans. I would come to learn that these cities would share more similarities than just transportation. I got dinner at a Lawsons, a competitor to my beloved 7-11, then headed to another competitor, Family Mart. Since it was cherry blossom season, Family Mart had a unique cherry creme-filled croissant which was possibly the best continual thing I ate while in Japan.

I returned to the hostel to have my dinner and my free drink when I struck up a conversation with James. James was a 27-year-old Welshman who was traveling through Asia before he headed back home to begin his professional training to deal with the coming regulation changes due Brexit. We shot the shit for about two hours, talking about everything from travel, New Orleans, South East Asia, Whales, David Simon, The Wire, Treme, and everything in between. As we chatted, I got a Suntory Highball, a canned, pre-mixed whiskey and soda, as well as two free sakes because James did not want his. Given my short stay in Hiroshima, he suggested I read this article from the New Yorker. He also said something which would stay in my mind. He said that after traveling through distant lands for months, he could not wait to get back home and be amazed about his corner of the world. He knew it would last for about a week before the shine wore off, but was eager to view his life with new eyes. He gave me his email and said I should look him up when I got to England. I wished him luck, headed for a constitutional, then took a shower. I settled in my pod and began reading the article until my eyes became heavy.

I woke up the next day, had another of those wonderful cherry blossom croissants, and explored this historical city. I crossed bridges over waterways, amongst forests, and walked by the river where there were people paddle boarding and boating. In the distance, I could see the still-standing skeletal remains of the building that had come to symbolize the power of man’s destruction. The Atomic Bomb Dome was once the central hub of Hiroshima. The Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall was built in 1915 and was located next to the Aioi Bridge, a very distinctive structure as it was a T-shaped. I would find out later that the bridge would be used as a guiding point for the bombing of the city.

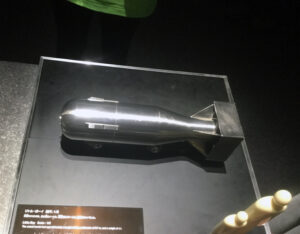

For the unfamiliar, at 8:15 am on August 6th, 1945, using this bridge, the first atomic bomb in human history was used on enemy targets. Of the two bombs built for war in the United States, the one used on Hiroshima was code-named Little Boy. As discussed in The Curve of Binding Energy, Little Boy was a gun-mechanism type bomb where a fissile reaction was created when an enriched Uranium 235 “bullet” was shot into a waiting core. Of the 64 kilos of Uranium used, under 1 attained nuclear fission, and less than a gram was converted to energy, concussive force, and heat greater than the core of the sun. This subsequently destroyed the city.

For the unfamiliar, at 8:15 am on August 6th, 1945, using this bridge, the first atomic bomb in human history was used on enemy targets. Of the two bombs built for war in the United States, the one used on Hiroshima was code-named Little Boy. As discussed in The Curve of Binding Energy, Little Boy was a gun-mechanism type bomb where a fissile reaction was created when an enriched Uranium 235 “bullet” was shot into a waiting core. Of the 64 kilos of Uranium used, under 1 attained nuclear fission, and less than a gram was converted to energy, concussive force, and heat greater than the core of the sun. This subsequently destroyed the city.

I then headed to the Peace Flame, Peace Pond, and Cenotaph, dodging the many people there asking me to sign their various petitions to end the use of nuclear weapons. Standing in front of the Cenotaph with a clear line of sight to the A-Bomb Dome, I said my little prayer as I promised myself I would if I ever got to Hiroshima. I then headed into the museum. Much like the Yasukuni Shrine, they seemed to leave out a lot of the reasons why this bomb was necessary. They mentioned a little of Manchuria but did not mention the imperial edict to repel invaders down to the last citizen. They also forgot to mention the projected death tolls of what an Allied invasion would entail; at least 1 million American soldiers and double or triple that of Japanese civilians. It also failed to mention that shortly after this bomb was dropped, the Soviet Union declared war on the Japanese. As proven across Europe already, they would no doubt subjugate the island to payback for their defeat during the Russo-Japanese War. Also, they would be a significant domino to fall in the global Communist expansion, blotting the Land of the Rising Sun behind an Iron Curtin. But, history is binary: either something happened, or it did not. While these bombs caused wanton destruction on an unimagined scale, it saved the lives of both the Allied Forces and the Japanese. Eschewing this fact, the museum said the bombs were dropped to justify their $2 billion price tag, $28 billion in modern dollars.

The museum also discussed the dangers of nuclear proliferation, even mentioning the mastermind behind it in the modern era, the Pakistani scientist Abdul Qadeer Khan. His greatest hits include starting successful programs in Libya, Iran, and North Korea. They also had cranes that Obama folded when he visited in 2016, sharing prattling platitudes about war, technology, and death, seemingly forgetful about his intimate relationship with them. I watched the speech back in my apartment in New Orleans. As he was talking about the hibakusha or people affected by the bomb and I thought of the words of another president, “That bomb caused the Japanese to surrender,” President Harry Truman, the man that ordered the bombs be dropped. “And it ended the war. I don’t care what the crybabies say now because they didn’t have to make the decision.”

I knew of the war crimes committed in Manchuria, the Comfort Women, and Unit-731, the military unit devoted to human experimentation on POWs; like attempting to replace their blood with seawater. I knew about the horrors my grandfather and many other grandfathers witnessed in the Pacific Theater. However, my heart softened by one particular artifact in this museum and its accompanying story.  There was a twisted, rusted tricycle contained within a glass case. Its owner, a three-year-old boy, loved this toy and would often spend his mornings traversing his family’s patio. Round and round he would go, as his adoring father would look on. That changed on the morning of August 6th. His house was not very far from the hypocenter, the spot in space where the bomb detonated for maximum effect, 600 meters above the city. The blast that would engulf the town would leave this innocent boy dead by the evening, succumbing to his wounds in his father’s helpless arms. There was no space for the city’s dead, and he did not want him to be alone. So, this father buried his son in their backyard with his most prized possession. In 1985, still weighted with the unimaginable grief of burying his child, the man had the body exhumed and moved to a more suitable resting place and donated the tricycle to the museum. I stood there, staring at the case, the fluorescent lights highlighting every spot of rust, paint, and possible blood, fighting back my tears. I said to myself an often repeated mantra when I was in these types of places both physically and emotionally, “God damn the men that make war necessary.”

There was a twisted, rusted tricycle contained within a glass case. Its owner, a three-year-old boy, loved this toy and would often spend his mornings traversing his family’s patio. Round and round he would go, as his adoring father would look on. That changed on the morning of August 6th. His house was not very far from the hypocenter, the spot in space where the bomb detonated for maximum effect, 600 meters above the city. The blast that would engulf the town would leave this innocent boy dead by the evening, succumbing to his wounds in his father’s helpless arms. There was no space for the city’s dead, and he did not want him to be alone. So, this father buried his son in their backyard with his most prized possession. In 1985, still weighted with the unimaginable grief of burying his child, the man had the body exhumed and moved to a more suitable resting place and donated the tricycle to the museum. I stood there, staring at the case, the fluorescent lights highlighting every spot of rust, paint, and possible blood, fighting back my tears. I said to myself an often repeated mantra when I was in these types of places both physically and emotionally, “God damn the men that make war necessary.”

After the museum, I headed to a subterranean memorial. A German couple would not stop laughing, so as became my custom, I starred them down until they shut up. I walked around the other memorials, including the one to children that developed various diseases due to radiation exposure. There is a Japanese custom of folding 1000 origami cranes so that whoever complete this task may ask a wish of the gods. Growing up in the immediate and later aftermath of the bomb, many children became inflicted with various forms of diseases: malnutrition, radiation poisoning, and cancer. I first learned of this in third grade when we were doing a unit on Japan reading Sadako and the 1000 Paper Cranes. While children were in hospitals, this activity gave them not only a way to stay busy, but also hope. Many would not see their wishes realized, however. I felt that my emotional capital had been spent for the day. So I continued on.

I walked to the Shukukein Gardens, but their entry fee was astronomical, so I headed over to Hiroshima castle. It was lovely and a needed respite from my morning of death and destruction. There were carps in the moat the size of large dogs that chomped their food with gusto. I then realized the reason for the name of the city’s baseball team. I headed to my hostel to rest a bit, then went to an interesting place for dinner, which was right down the street. The chefs were very hospitable as we were unable to communicate, and again, I resorted to grunting and pointing. Using Google, they asked me to help translate part of their English menu, which was fun. I then went back to my hostel and enjoyed a very much needed tall glass of free sake.

over to Hiroshima castle. It was lovely and a needed respite from my morning of death and destruction. There were carps in the moat the size of large dogs that chomped their food with gusto. I then realized the reason for the name of the city’s baseball team. I headed to my hostel to rest a bit, then went to an interesting place for dinner, which was right down the street. The chefs were very hospitable as we were unable to communicate, and again, I resorted to grunting and pointing. Using Google, they asked me to help translate part of their English menu, which was fun. I then went back to my hostel and enjoyed a very much needed tall glass of free sake.

The next day was a bit of a lazy one. I awoke, rolled around in bed with my iPod, then headed out. I wanted to head to the bus station to figure out how to get to Nagasaki, and I also wanted to find some Carps gear. New Orleans and Hiroshima are in a unique club where the cities have become synonymous with wanton destruction, yet were able to pick themselves up with the aide of sports. The Hiroshima Toyo Carps was founded in 1950 and later sponsored with the help of a little local car company called Mazda. Every type of merchandise was available, including plush dolls of their mascot who has an incredible likeness to someone else I know. I settled on a keychain as jerseys were too expensive.

After, I got lunch and chilled for a bit then did some laundry. As the next day was a long ride, I needed to get some supplies. I headed back to the hostel for my free drink after eating my dinner. When I arrived and saw a large group sitting at the bar, I knew exactly where they were from. Having lived in Los Angeles for my mid-20’s, I know how to spot locals: usually loud, raucous, and off-putting until you strike up a conversation, then (most of the time) they are quite amiable.

After the sake flowed, we all became friends. One of the Los Angelinos asked our hosts what the Japanese thought of Americans. I chimed up that this was probably the wrong city to ask. Through the prism of 75 years of peace between our two nations, everyone had a good chuckle. I excused myself from my new friends as I had to go to bed early for my trip to Nagasaki.